Classic Car Reviews: Oldsmobile Jetfire

Turbocharging had become commonplace today, but back in 1962 the Oldsmobile Jetfire’s turbo V8 was novel technology for production cars.

Turbocharging the Future

Today you can find turbochargers in everything from everyday rides like the Ford Eco Sport and Toyota Tacoma to specialty performance cars like the Mercedes-AMG GT and Porsche 911 Turbo. Turbos were not always so ubiquitous. Once upon a time, turbochargers were the province of airplanes and heavy-duty diesel trucks but not production cars. It wouldn’t be until the 1960s that we first saw turbocharging in mass produced passenger cars like the Oldsmobile Jetfire.

Force induction, forcing additional air into the combustion chamber for more power, had been around for decades. Supercharging was initially developed in the late 19th century and had been in widespread use since the 1920s on pre-war European racecars like the Mercedes SSK, Bugatti Type 35, and Bently 4.5L “Blower” as well as high-end American luxury cars like the Auburn Speedster and Duesenberg SJ.

It took several more decades for automotive technology to evolve to the point where turbocharging became feasible for production cars. Modern turbocharging is as much about preserving output while increasing efficiency as it is about added “performance.” Which is why you’ll find turbos implemented in all sorts of non-performance vehicles.

Turbos are any easy way to coax 200+ horsepower from otherwise anemic four-cylinders while maintaining good fuel economy. And so it was with the very first turbocharged V8 production car, the 1962 Oldsmobile F-85 Jetfire, which gave the Cutlass’s 215 cu.-in. V8 a much-needed boost without transforming it into a performance car.

The Jetfire’s Turbo V8

The Oldsmobile Jetfire was not the only car pioneering turbocharging in early 1962. Its GM cousin, the Corvair Monza Spyder, featured a turbocharged flat-six and was released within weeks of the Jetfire. The Jetfire was based off Oldsmobile’s F-85 compact platform utilizing the same body and interior as the Cutlass and priced at $3,408, about $350 more than the Cutlass.

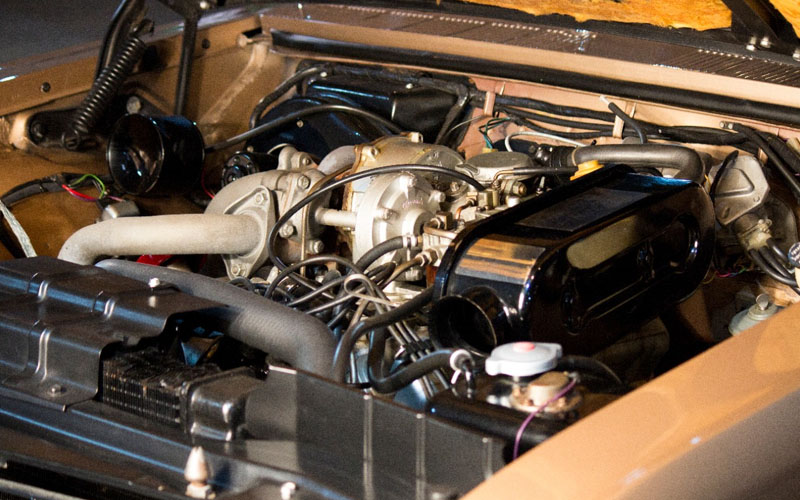

The difference was of course the new turbocharged 215 cu.-in. V8. In its basic form, the all-aluminum 215 V8 shared across GM’s Y-body cars produced 155 horsepower and 210 lb.-ft. of torque. A four-barrel version for the Cutlass netted 185 horsepower. Implementing a turbocharger allowed the Jetfire’s version of the 215 V8 to hit 215 horsepower and 300 lb.-ft. of torque. Gearing was provided by either a four-speed Borg-Warner manual transmission or a three-speed HydraMatic automatic.

The turbocharger came courtesy of Garret AiResearch (which had extensive experience building turbochargers for heavy duty diesel engines) and applied a modest 5 psi of pressure. (For context, the Ford EcoBoost 2.3L typically runs about 20 psi of pressure.) Oldsmobile’s engineers decided to maintain the 215 V8’s relatively high 10.25:1 compression ratio, despite the increase in pressure from the turbocharger. This presented a potentially catastrophic problem: engine knock. To prevent very much unwanted ignition outside the regular Atkinson cycle, the engineers devised a now common solution with a not so common name: “Turbo-Rocket Fluid.”

Turbo-Rocket Fluid

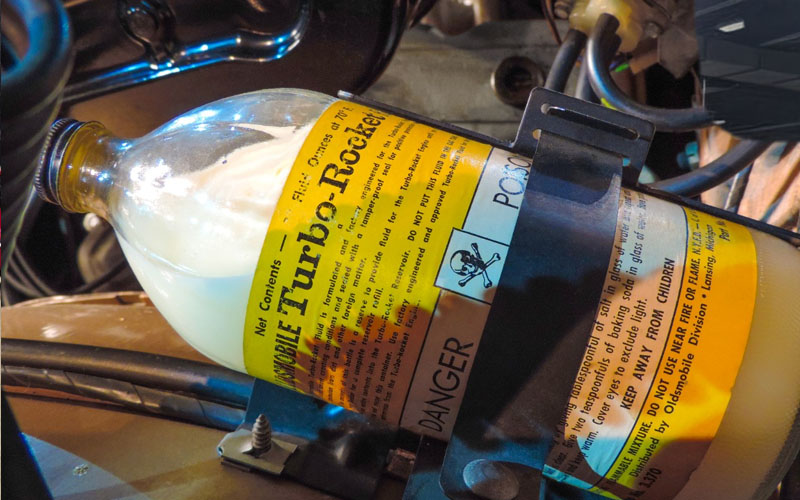

The cleaver branding obscured the necessity of the engineering workaround. The so-called “Turbo-Rocket Fluid” was not, obviously, rocket fuel but instead a 50/50 mixture of methanol and water, with a dash of anti-corrosion agent, that was sprayed into the air-fuel mixture, cooling it enough to prevent unwanted ignition. Owners had to fill up the Turbo-Rocket Fluid reservoir every 300 or so miles.

Oldsmobile’s official estimate was between 300 and 3,000 miles, depending on how hard the car was driven, though most accounts point to fewer than 500 miles before a refill of the five-quart reservoir was needed. Owners then had to return to the dealership for a top-off of Turbo-Rocket Fluid. While inconvenient, engineers wisely implemented a failsafe: an additional butterfly valve on the throttle body acted as a boost limit control valve for the turbo, closing it off from the system when your Turbo-Rocket Fluid ran low.

Legacy of Jetfire

The Oldsmobile Jetfire only managed to see two model years of production before its cancellation. Not only did owners not like having to constantly top-off the Turbo-Rocket Fluid or suffer a notable diminishment of power, but Oldsmobile found larger naturally-aspirated V8s could easily provide even more power than current turbocharging technology and with considerably less complex engineering.

Despite the short run for the Jetfire, it was an invaluable proof of concept. The Jetfire’s light weight (just 2,860 lbs. wet) and turbo-boosted engine provided a template for future turbocharged performance cars. While turbocharging continued to see implementation and further development in motorsports, it took another decade before turbos began arriving in performance road cars like the BMW 2002 Turbo of 1973 and 1975’s Porsche 930 Turbo, both of which, like the Jetfire, were lightweight and maximized their power with the help of turbochargers.

A total of 9,607 Oldsmobile Jetfires were built across a scant two model years and just 120 remain extant today with fewer than 50 retaining functioning turbochargers.