Lead Sleds and the Hirohata Merc

Chopped, channeled, and sectioned, lead sleds like the Hirohata Mercury set the mold for early custom cars.Making it Your Own

Cars are, and have always been, primarily a mode of transportation, a kind of point A to point B thing. But throughout their history, cars have also served as a mode of self-expression. Your wheels tell the world who you are, perhaps where you’re from, and often what you value. Custom cars express their owners’ specific automotive values, whether that be honoring a specific tradition, demonstrating a builder’s ingenuity, or showcasing the singular vision of their designer.

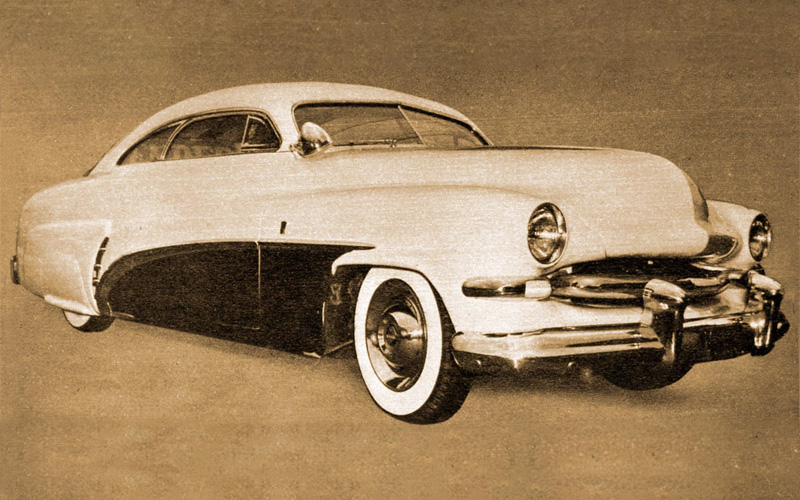

Lead sleds, the earliest custom cars, emerged in the middle 20th century often, built from ‘49 Ford and Mercury 8s. Their “chopped” rooflines and leaded bodies imaginatively restyled contemporary cars for a look and feel unique to their owners. No other lead sled was as influential in its day or as heralded over the decades as the quintessential example of the Hirohata Merc.

Lead Sled Genesis

Custom cars first emerged as a major force in American automotive culture in the mid-1940s following WWII. This new trend involved heavily modifying bodywork, an expensive and technically intensive endeavor that contrasted with hot-rodding, which focused less on aesthetics and more on pure speed.

Though hotrods had been around for a while, both they and custom cars were becoming increasingly popular in those post-war years. A whole generation of young men, many of whom had returned from the war with newly acquired mechanical and metalworking skills, were ushering in the first golden age of aftermarket modification.

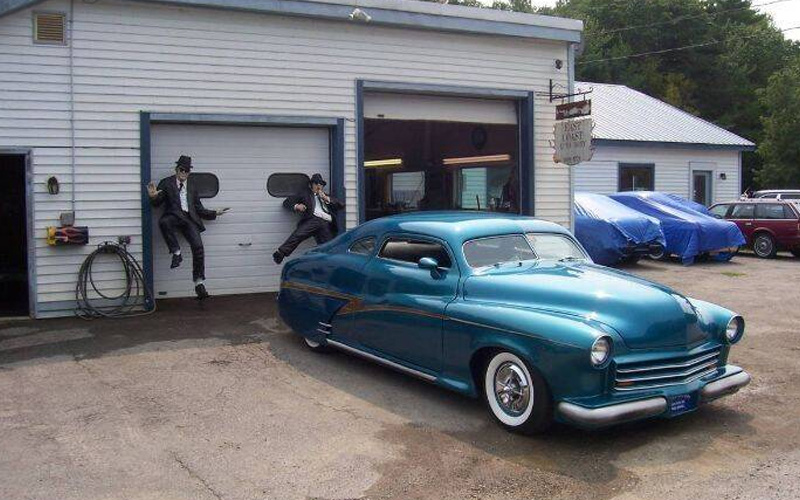

The “lead sled” phenomenon began in California with the first “chopped” Mercury modified by Sam Barris in Los Angeles in 1949. Barris and his brother George quickly made a name for themselves as the area’s premier customizers. The lead sleds were so named owing to the use of lead as a body filler, this being prior to the advent of Bondo.

Typically, lead sled style cars “chopped” the roof, lowering it three inches or more, “channeled” the chassis so that the body sat lower on the frame, and “sectioned” the body, basically removing a whole center section of the body paneling all the way around the car. Other common modifications included Cadillac hub caps, Appleton spotlights, and an engine swap for greater power (the Mercury engines were known to be underpowered for the car and prone to overheating). Grilles were modified while door handles, hood ornaments, and other brightwork were deleted. The “chopped, channeled, and sectioned” modifications accentuated the Mercury’s aerodynamic, slipstream looks.

The Hirohata Merc

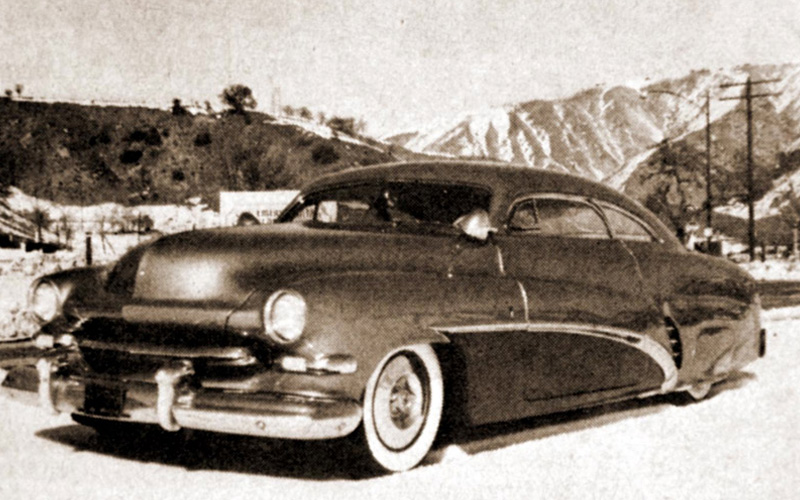

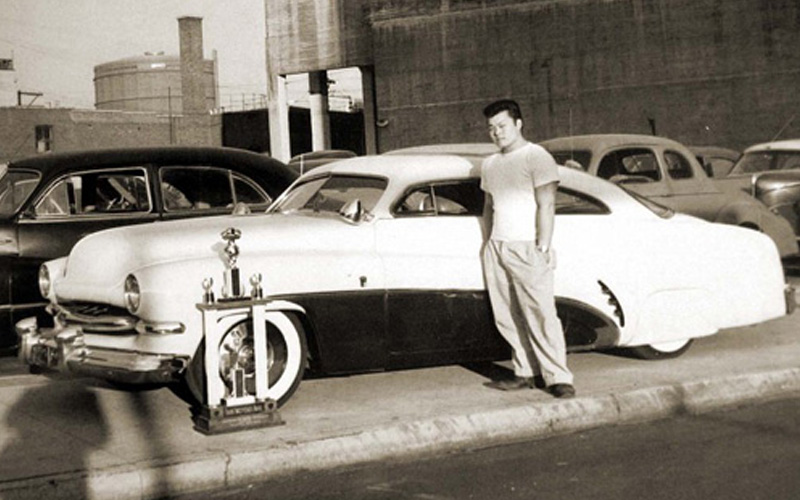

All these elements can be seen on the most iconic and influential of lead sleds, Masato “Bob” Hirohata’s 1951 Mercury. Hirohata liked the custom car look and when he decided to commission his own, the logical choice was to ask the Barris brothers to do it. The two brothers’ workshop was well known for the quality and inventiveness of their customs, with the elder Sam a bodywork master and younger George a wiz at both design and promotion. (George would, of course, go on to design the 1960s Batmobile, the Munster Koach, and many more custom cars for film and television.)

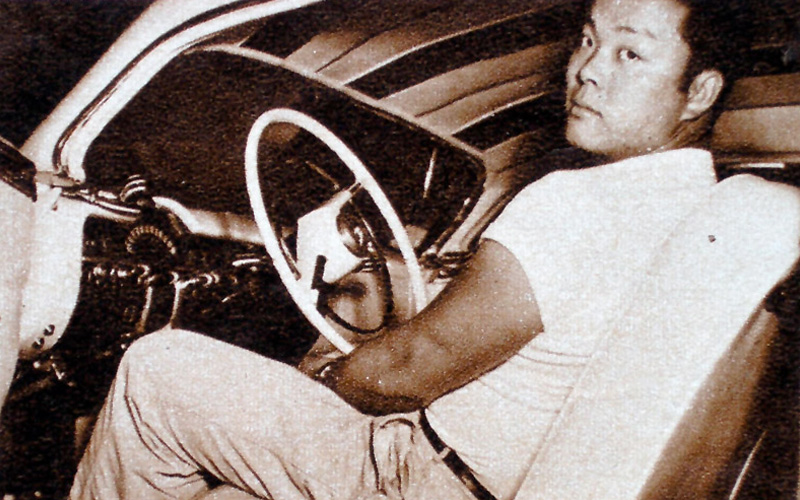

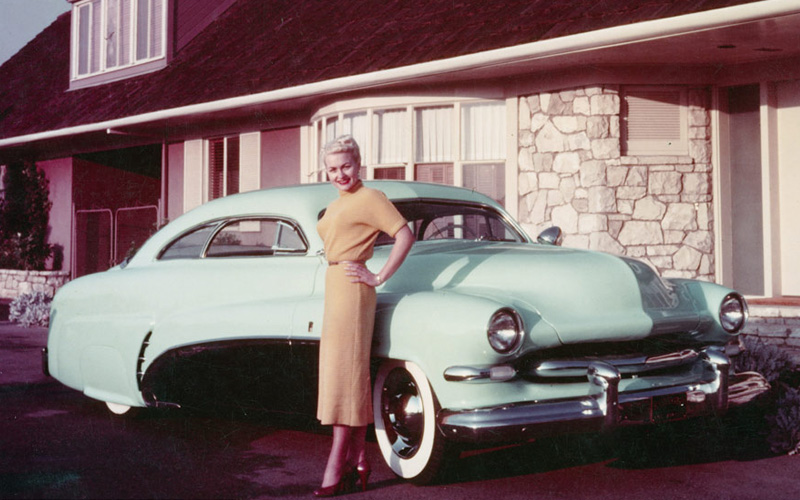

As was common for custom car projects, Hirohata bought a new ’51 Mercury for modification and brought it to the Barris’ shop along with his requests for the build, including a green-on-green two-tone paint scheme. Busy as he was, Sam Barris dragged out the build, completing other work as the Hirohata project lingered. That was until Hirohata made clear his desire to show the car at the upcoming Motorama car show, in two weeks’ time. Sam, George, and the rest of their team toiled relentlessly to meet the deadline, with up to ten of them at a time working on the car. Not only did they complete the car on time for the show, but the results of their labors became the stuff of automotive legend.

Customizing the Ultimate Custom Car

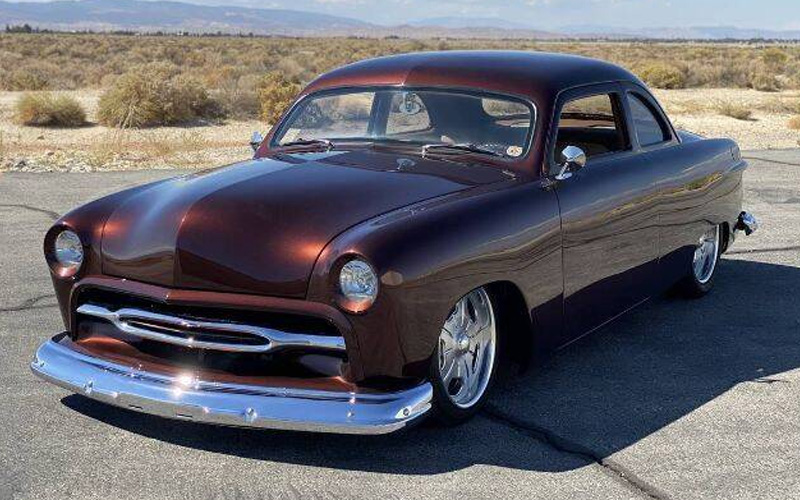

The Hirohata Merc possesses a perfect balance of original and custom elements, a hallmark of lead sled designs. Unlike the gaudy, overwrought customs of the 21st century (think West Coast Customs or Pimp My Ride), these early custom cars took a more subtle but no less radical approach, chopping and reshaping bodies and augmenting them with various borrowed parts all while ensuring that the final design was as cohesive as it was head-turning. Like all great art, the Hirohata Merc synthesizes the familiar with the unexpected for something rings true while at the same time striking a new, as-yet-unheard note.

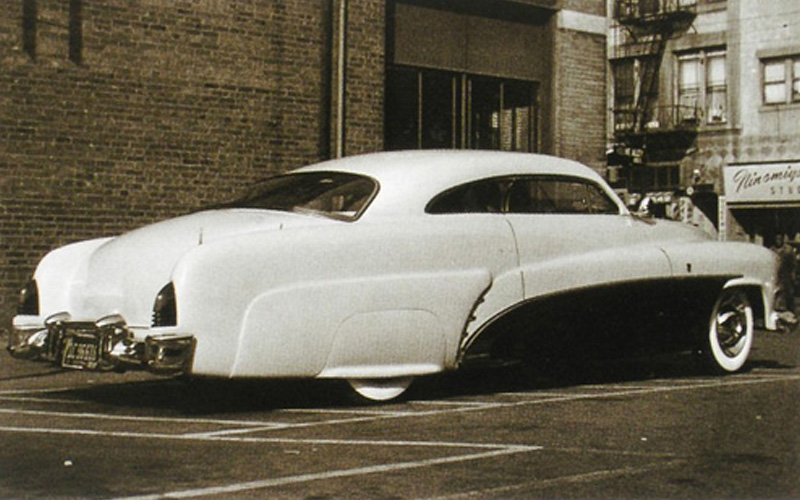

Coherent as the final product is, the Hirohata Merc is a surprisingly eclectic mix of elements. The first thing you note about the car, and lead sleds like it, is the chopped top. The Hirohata Merc’s roof is dropped with a rearward angle, lowered seven inches in the rear and four in the front. The rear window is original, slanted to meet the newly created slope. The midline of the car is also lowered, creating a new longer and more continuous line from front to back. Of course, the frame is also lowered with the rear fender cover nearly eclipsing the rear tires. The result is one of those classic “looks fast standing still” profiles.

The car borrows many of its most distinctive parts. The side trim pieces are reversed, upside-down Buick “side spears,” a popular addition to lead sleds. These pieces also replace the deleted door handles, activating solenoids to unlatch the doors. Those aren’t folded side mirrors on the sides of the car, those are Appleton spotlights, tastefully folded down. The car’s floating grille is the first of its kind on a custom car. It’s comprised of parts from three ’51 Ford grilles. The teeth in the fender scoops are off a ’47 Chevy. (Notably, the pair of fender scoops are not symmetrical as they were made by two different workers in the rush to finish the car.) The hubcaps, as the emblem indicates, are Cadillac in origin as is the car’s replacement motor, a 331 Cadillac V8, installed in 1953. The taillights are those of a Lincoln Capri.

Other custom features on the car include a pair of castor wheels in back to prevent bottoming out the rear end and integrated tailpipes in the bumper. The redesigned hood carries the biggest share of the car’s lead filler as the design brings the lip down several inches lower than the original. Bob Hirohata commissioned green plastic knobs for the dash instrumentation to match the car’s color scheme. The car’s two-tone pastel green and dark green paint job was a marked departure from the blacks and maroons that were most common on lead sleds at the time. A final late edition was the Von Dutch pinstriping done on the glovebox in 1955.

What Happened to the Hirohata Merc?

Bob Hirohata took his newly customized Mercury not just to Motorama but countless other car shows, traveling all over the country and building the car’s reputation as a custom second to none. It appeared on the covers of major auto magazines. George Barris’ promotional skills even got the car featured in the B-movie Running Wild, starring Mamie Van Doren (he repainted the car an avocado green for better contrast in black and white).

But as with any car, its owner grew bored with it and eventually Hirohata sold off his prize-winning custom Merc. The car passed from owner to owner for the next few years as the popularity of custom cars waned. The Hirohata Merc eventually ended up in a used car lot where it caught the eye of highschooler Jim McNeil in 1959. McNeil bought the car for $500 dollars and used it as his daily driver as a teenager. He kept the car for decades as a prized possession, always intending to refurbish it and turning down numerous offers to sell the historic car.

Many years on, McNeil was contacted by Pat Ganahl. Ganahl had long wondered what had happened to the Hirohata Merc, finally tracking it down to McNeil to whom he proposed a restoration project. With the help of Ganahl, McNeil’s long deferred restoration of the Hirohata Merc was finally on. Not only did McNeil get help from Ganahl, but he also contacted some of the Barris shop’s original workers, including Hershel “Junior” Conway and Frank Sonzogni, who helped bring their decades of experience and first-hand knowledge to bear on the project.

The restored car again toured the country and then the world, garnering a spot on the National Historical Vehicle Registry (#17 of 29) and winning its class at the Pebble Beach Concourse in 2015. With Jim McNeil’s passing in 2018, the car was sold at auction for the princely sum of $1.95 million in 2022.