Retro Review: Chevy Camaro IROC-Z

For ultimate 80s styling, the Camaro IROC-Z is hard to beat.

The T-Top of the Heap

80s nostalgia is having something of a moment. From Millennials with rose colored glasses to Gen-Zers digging on “old stuff” chic, the decade of shoulder pads and synthesizers hasn’t been cooler since, well, the 80s. And the auto aftermarket has certainly not been immune to the trend. The automotive styles of the 1980s are red hot, with cars like the Countach, E30 M3, and Porsche 944 gaining newfound prestige.

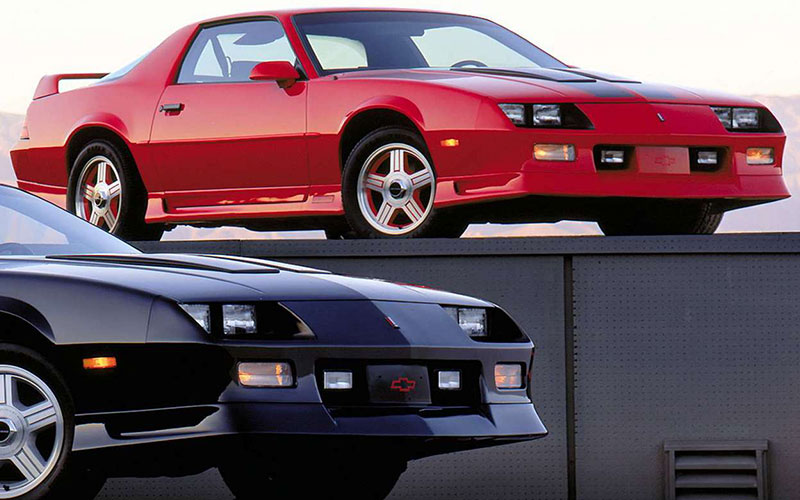

But it’s not just European sports cars that carry the distinctive 80s look forward into today. The instantly evocative Camaro IROC-Z will bring you back to 1985 faster than Doc Brown’s DeLorean. Indeed, the IROC-Z’s styling is more 80s than hair bands, John Hughes movies, or catchphrases like “Where’s the beef?”.

Today, we look back on the top-of-the-line Camaro from a decade of largely forgotten muscle cars.

A Third Generation Begins

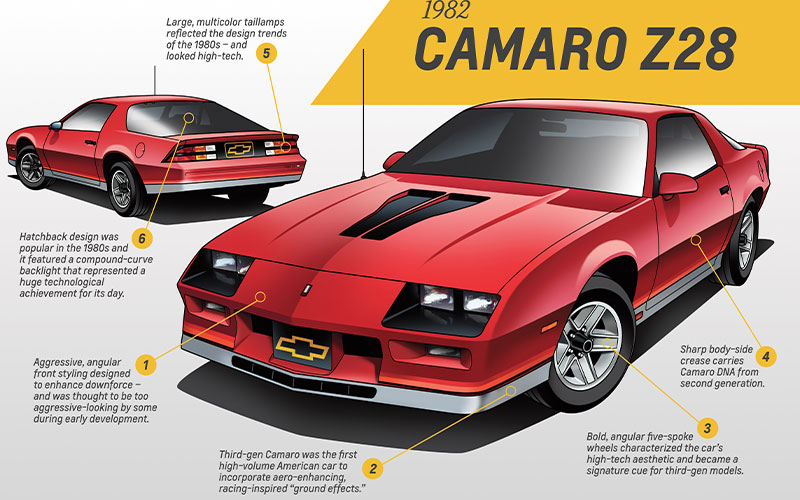

Chevy’s third-generation Camaro was a radical departure, officially debuting in 1982. Though sharing the prior F-body platform, the new Camaro featured a strikingly modern design with a sharply racked windshield, long hood, new hatchback body style, and optional fuel-injection. One thing hadn’t changed, however. This was still the tail-end of the Malaise Era, and the new Camaro suffered from the same lack of horsepower that late second-gen cars had. Though the decade known for its weak performance cars, the Camaro would see a modest yet steady uptick in power as the 80s went on.

Even without a ton of power, the 1982 Camaro Z28 was named Motor Trend’s Car of the Year. The handling was good and styling, as we’ve mentioned, was off the charts. The base Camaro Sport Coupe came standard with a 151 cu-in inline-four, with options for a V6 or a 305 V8. That 305 was the standard engine in the Z28 and made … 145 horsepower. And yet, the Camaro was a sales success for Chevy, even without the performance.

Birth of the IROC-Z

But what about the IROC-Z, you ask? For that story we need to look back a few years, to 1974.

IROC-Z stands for International Race of Champions and Z, because, if the naming conventions of snack foods and soda pops has taught us anything, it’s that adding a Z or X at random automatically makes things sound 25 percent cooler.

The International Race of Champions began in 1974 as a sort of racing all-star competition, with drivers from across the spectrum, from NASCAR to Le Mans and everywhere in between, competing in the same car to prove whose skills behind the wheel were truly superior. For the inaugural race, organizers went with the Porsche Carrera RSR. They switched to the Chevy Camaro the following year and up to 1980, when the race when on hiatus. In 1985, the International Race of Champions was set to return, again with the Camaro as the car. Chevy took the marketing opportunity to offer a new, upgraded version of the Z28 and dubbed it the IROC-Z.

For just an extra $659 dollars, the IROC-Z got Camaro buyers a lowered, upgraded suspension, Bilstein shocks, stouter sway bars, and optional Tuned Port Injection (TPI) for the 305 cu-in V8. Both it and the Z28 got a low front spoiler and fake, but stylish, hood louvers. Specs were impressive (for the day) with the 305 putting up 215 horsepower and 275 lb-ft of torque and netting .90g on the skid pad.

Year-By-Year Changes

Not a lot changed for the 1986 IROC-Z. A subpar LG4 camshaft sapped the car of some 25 horsepower. In keeping with new safety regulations, Chevy added a new 3rd brake light above the rear hatch.

The following year proved more consequential. New hydraulic roller camshafts were installed for all the optional engines, improving output and fuel economy. Meanwhile, the IROC-Z got a new engine option, a TPI 350 cu-in V8 from the Corvette making 225 horsepower and 330 lb-ft of torque. Both the IROC-Z and Z28 received new140-mph speedometers (versus the 85-mph version on the V6 car). Absent since the late 1960s, the 1987 model year also saw the return of the convertible body style to the Camaro, built by converting the T-top bodies (did we mention the 3rd-gen Camaro had T-tops?).

For 1988, the Z28 was discontinued, leaving just the base model and the IROC-Z for Camaro trims. The IROC-Z got an upgraded camshaft, 16-inch wheels, and the V8s ticked up in power with the automatic-equipped 305 up to 195 horsepower and the 5-speed manual to 220 horses. The automatic-only 350 was bumped to 225 horsepower. Fuel-injection was now standard across the board.

Power increased again in 1989, with the 305 hitting 230 horsepower while the 350 reached 240 horsepower and a stout 345 lb-ft of torque. 1990 would be the final year for the IROC-Z. A new 1LE performance package was offered and included an aluminum driveshaft, four-wheel disc brakes with aluminum calipers and 12-inch front rotors, a 3.42 posi rear end, updated anti-roll bars, and an engine oil cooler. The 350 finished its IROC run with 245 horsepower and 345 lb-ft. Chevrolet replaced the IROC-Z with the returning Z28 for the 1991 model year. The substitution resulted from the fact that Dodge had taken over sponsorship of the International Race of Champions and the Dodge Daytona had replaced the Camaro as the car of choice.

All Show, Some Go

Was the IROC-Z the fastest Camaro ever built? Not by a long shot. But was it among the coolest and most distinctive looking? Surely it was. It’s hard to judge old muscle cars, or more generally old sports cars, by modern standards. With the benefits of today’s technology, all manner of commuter cars with 2.0L turbos are putting out equivalent or better numbers compared to many of the “classics.” But like the sports stars of yesteryear, we need to judge cars within the context in which they existed. And by that standard, the IROC-Z was totally gnarly, radical, and/or bodacious.