Tucker 48: Wild and Way Ahead of Its Time

Preston Tucker defied convention and Detroit automakers with his revolutionary Tucker 48, but sometimes innovation alone isn’t enough.

The Original Automotive Maverick

Mark Twain is often credited with the aphorism: “History doesn’t repeat itself, but it rhymes.” When it comes to challenging the hegemony of Detroit’s Big Three, automotive history is littered with smaller upstarts who never quite found their footing, despite their innovative ideas. You know the story of John DeLorean and his DMC-12, and before him Malcom Bricklin and his SV-1. Their stories, to use Twain’s phrase, rhyme with that of an earlier automotive maverick, Preston Tucker and his Tucker 48. Like DeLorean and Bricklin, Preston Tucker was a magnetic figure full of big ideas and a zeal for upending the status quo. Tucker, like DeLorean and Bricklin, did not ultimately succeed, but the car that bears his name was marvelously ambitious, perhaps too ambitious.

Tucker, From Cop to Car Salesman

Preston Tucker, born in 1903, was interested in cars from an early age, reportedly learning to drive at just 11 years old. One of his first jobs was working as an office clerk for Cadillac. A stint as a police officer might seem a diversion from his life’s path, but Tucker’s biggest interest in joining the force was to ride around town on a motorcycle, one that he wound up modifying. While Tucker was an effective law officer, he became notorious for his fast driving and his obnoxiously loud motorcycle. At his mother’s behest, he was eventually fired for having lied about his age on his application.

Tucker later worked on Ford’s assembly line and sold Studebakers before returning to law enforcement. He was fired again, this time for modifying his patrol car, blow-torching a hole in the dash to allow in heat from the engine bay on cold Michigan nights. Once more, Tucker turned to selling cars. His charisma and enthusiasm helped him excel and he worked for numerous dealers, selling Studebakers, Stutzs, Pierce-Arrows, and Dodges, eventually elevating to the role of regional sales manager.

It was during his time selling cars that Tucker began attending races at the Indianapolis 500. There Tucker became acquainted with an increasing number of racecar drivers, mechanics, and engineers. One of those engineers was Harry Miller, a renowned designer of many of the Indy 500s most successful engines. Miller was not, however, as financially successful as his mechanical creations. He and Tucker went into business together and were briefly contracted to build Ford racecars (which fell through) before starting work together in Ypsilanti, Michigan in the late 1930s designing armored cars, gun turrets, and other hardware to sell to the US military.

None of their designs ever ended up in use, but the “Tucker Turret” came close, and their armored car design was picked up by the Dutch. Unfortunately, the Netherlands were invaded by the Nazis and Tucker was not able to make good on the contract. Tucker pivoted to aviation with the Tucker Aviation Corporation which developed a new fighter plane design and was eventually acquired by Higgins Industries of New Orleans, LA. Tucker served as the company’s vice-president for a time, but his relationship with Higgins soured and he moved back to Michigan in 1943.

Fomenting an Automotive Revolution

It was upon his return to Michigan that Tucker began working toward founding his own car company. With automotive production halted due to the war, he knew there would be pent up demand following the war’s conclusion, and Detroit’s Big Three would need time to pivot back from building tanks and airplanes to building cars.

Tucker’s plan was to build a “car of the future” that pushed the envelope not only in styling but in safety and engineering as well. The styling component came from George S. Lawson, who’d worked for GM’s Buick division. Tucker planned for a novel, yet practical car to seat six people and feature a rear engine configuration. With a clay mockup in hand, Tucker began promoting the car to potential investors, photographing the model from a forced perspective to make it appear like a life-size prototype.

Another major early step came when Tucker bid on a former Dodge plant in Chicago that had been used for wartime production and was now held under the auspices of the War Assets Administration. It turned out Tucker was the sole bidder and won by default. Which would have been great except he lacked the operating capital in escrow required, $15 million, to take over the lease.

Tucker, ever the savvy salesman, began to sell dealership and distribution rights to drum up funds, netting around $6 million. This move prompted the first, but not the last, investigation by the SEC (Securities and Exchange Commission) into Tucker’s fund-raising practices. To make up for the still considerable gap in funding, Tucker launched a stock IPO, one of the first such public offerings. This in turn led the SEC to require Tucker to produce a working prototype of his car.

The Wildest of Automotive Dreams

Tucker’s ambitious plan to found a new US car company was almost as ambitious as the car he envisioned as its first product. Lawson’s initial design featured unusual elements. In addition to the rear-engine and even a novel third headlight, the Tucker Torpedo as it was first called, was to have pivoting front fenders. Tucker’s wish list of innovative features for the Tucker Torpedo was long. In addition to the rear engine design, he wanted four-wheel disc brakes, fuel injection, and a fully independent suspension. Safety was also core to the car’s pitch and so Tucker planned pop-out windshield panels, a padded dash, doors cut into the roof for easy ingress/egress, and an integrated rollbar. Then there was the Tucker “safety cell” created by moving all instrumentation to the far left and putting glove boxes in the door panels, leaving a lot of space for passengers to tuck in under the high padded dash in a collision.

As with many of Tucker’s working relationships, he and Lawson fell out and Alex Tremulis, designer of the Cord 810/812 came in to refine and finish the design. Tremulis eliminated the pivoting fenders which would have made the car unstable at high speed (having the center headlight pivot instead) and refashioned the car’s roof line and other elements.

Most radical of the Torpedo’s plan was its drivetrain. Tucker’s idea was to use a 589 cu.-in. flat-six cylinder with hydraulic lifters and a pair of hydraulic torque converters on either of the rear wheels rather than a traditional transmission. Idle for the engine was an unusually low 100 rpm with peak output coming in around 1,000 rpm. Tucker’s engineers had a lot of trouble with the engine which required a 24-volt electrical system and required extremely high pressure for the hydraulics to work properly.

Financial circumstance required Tucker to press forward on his fund-raising efforts despite the half-baked nature of his first prototype nicknamed the Tin Goose. As the Torpedo name carried too many negative connotations in those post-war years, the car’s official name was changed to the Tucker 48, after the year of its planned release.

A Rough Start for the Tucker 48

Tucker promoted the car as “the first new design in 50 years,” and the result of “15 years of rigorous testing” and public interest was high for a shiny new alternative to the pre-war designs coming out of Detroit. Such hyperbole was good for garnering attention, too bad for Tucker, it also caught the attention of the SEC.

The Tucker 48 debuted on June 19th, 1947, in Chicago, with more than a hitch or two. The car’s first problem cropped up the night before when two suspension arms snapped. At the next day’s premier, Tucker had a live band playing in the background to help mask the loud, unrefined note exhaust of the car which he had to keep running through the debut because it often took several minutes to get the sputtering, low-revving engine started at all. The prototype didn’t even have a reverse gear.

Even christening the car with a bottle of champagne went awry when the woman tasked with smashing the bottle on the front of the car did so not from up to down but across the front, showering the front of Tucker’s suit with champagne and glass. Unsurprisingly, the press for the event was not good, with some reporters wondering aloud whether the whole thing was nothing more than a grift.

Undeterred, Tucker continued development on the Tucker 48 and his efforts to raise more funds. As Tucker and his team worked on building more and more refined prototypes practical necessities require changes to the original design. Fully independent suspension was never realized, though an unusual rubber torsion beam set up was used. Disc brakes and fuel injection never materialized either.

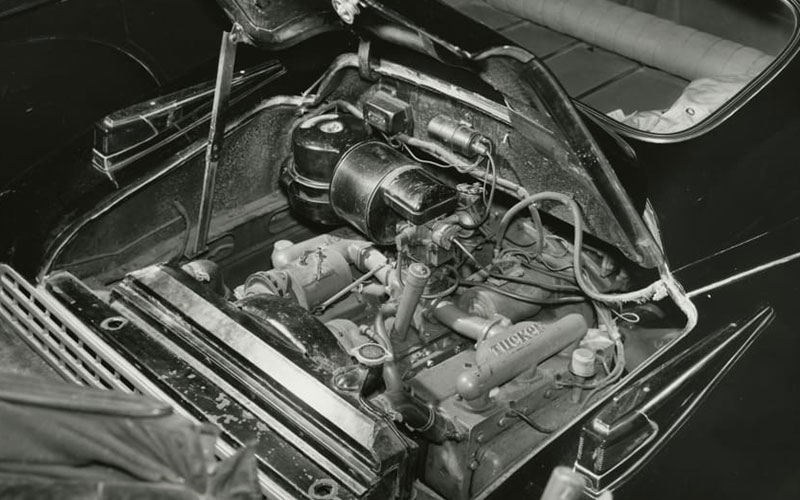

Most significant of the mechanical changes was a switch in engines. The 589 flat-six was too much trouble and so Tucker went shopping for an alternative which he found in the form of a Franklin helicopter engine built by Air-Cooled Motors. To secure this vital engine supply, Tucker went ahead and bought out Air-Cooled Motors for $1.8 million. At the time Air-Cooled Motors held roughly 65% of all post-war aeronautical engine production contracts in the US. In the rashest business moves, Tucker promptly canceled those aeronautical contracts so Air-Cooled Motors could concentrate solely on developing and producing the Tucker 48’s engine, effectively forgoing otherwise lucrative business to chase the dream of his revolutionary new car.

Equally inexplicable, Tucker decided that the new air-cooled engine, already destined for the rear of the Tucker 48, would be converted to liquid cooling, requiring major re-engineering of both the engine and the car’s cooling systems. Rather than the torque converter set up, prototypes were fitted with Cord transmissions as a stopgap measure while engineers worked designing a new “Tucker-Matic” transmission.

Dreams Meet Reality (and the SEC)

Meanwhile, Tucker was hard at work trying to keep money coming into the company. Tucker came up with a new revenue stream involving selling components to future cars to prospective customers. These usually came in the form of car radios or luggage, the idea being customers could get a piece of their future car today along with a preferred spot on the waiting list.

This tactic was the last straw for the SEC which indicted Tucker and his executive team for fraud. Between the bad press from the shoddy prototype debut and the SEC charges, company coffers ran dry. Just 37 prototypes had been completed before work was concluded at the Chicago facility, though another 13 cars would be built by loyal employees soon thereafter.

Just 50* Tucker 48s were built. Tucker and his team eventually prevailed in court and charges were dropped in January of 1950, far too late to save the company and the Tucker 48. For his part, Tucker remained undeterred, drumming up new business in Brazil to build a car there prior to his premature death from lung cancer in 1956.

Today, an estimated 47 Tucker 48s are still existent. One is owned by director Francis Ford Coppola, who made the 1988 film Tucker: The Man and His Dream starring Jeff Bridges. The central plot of the movie pits the plucky Tucker against Detroit’s Big Three automakers who are bent on preventing the upstart Tucker from challenging them on equal footing, using their political connections to spur an SEC investigation. Whether or not Coppola’s version of events bears resemblance to reality, what rings true is his the depiction of Tucker as the consummate salesman, an innovator, and a dreamer of the highest order.